|

| |

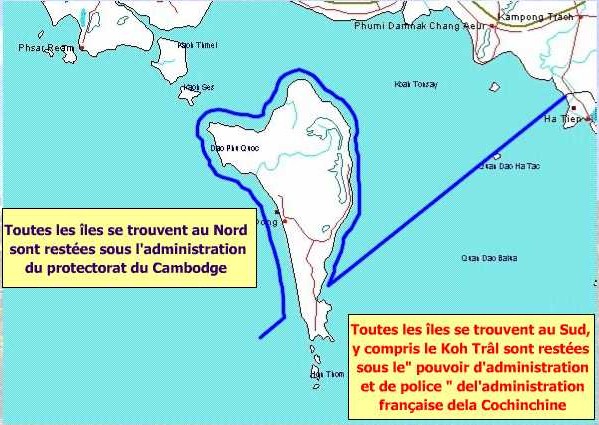

Hải-phận Việt-Nam và Khmer

phân-chia theo đường Brévíe

Hải-phận với Campuchia

Trong buổi Hôi Thảo về Phát Triển Khu Vực

Châu Á Thái B́nh Dương và

Tranh Chấp Biển Đông ngày 15 và 16 tháng 8 năm 1998 tại New York City

Ông Lê Minh Nghĩa

Nguyên Trưởng ban Ban Biên giới của Chính phủ VN đă

tŕnh-bày về

NHỮNG

VẤN ĐỀ VỀ CHỦ QUYỀN LĂNH THỔ GIỮA

VIỆT NAM VÀ CÁC NƯỚC LÁNG GIỀNG

Ông Nghĩa

đă phát-biểu

về việc thương-thuyết hải-phận với Campuchia như sau:

Trước năm 1964, quan điểm cơ bản

của phía Campuchia về biên giới lănh thổ giữa hai nước là đ̣i Việt Nam trả lại

cho Campuchia 6 tỉnh Nam Kỳ và đảo Phú Quốc.

Từ năm 1964 - 1967, Chính phủ

Vương quốc Campuchia do Quốc trưởng Norodom Sihanouk đứng đầu chính thức đề nghị

Việt Nam công nhận Campuchia trong đường biên giới hỉện tại, cụ thể là đường

biên giới trên bản đồ tỷ lệ 1/100.000 của Sở Địa dư Đông Dương thông dụng trước

năm 1954 với 9 điểm sửa đổi, tổng diện tích khoảng 100 km2. Trên biển,

phía Campuchia đề nghị các đảo phía Bắc đường do Toàn quyền Brévié vạch năm 1939

là thuộc Campuchia, cộng thêm quần đảo Thổ Chu và nhóm phía Nam quần đảo Hải Tặc.

Trong năm 1967, Việt Nam Dân chủ

Cộng hoà và Mặt trận dân tộc giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam đă chính thức công

nhận và cam kết tôn trọng toàn vẹn lănh thổ của Campuchia trong đường biên giôi

hiện tại (công hàm của Việt Nam không nói tới vấn đề chủ quyền đối với các đảo

trên biển và 9 điểm mà Campuchia đề nghị sửa đổi về đường biên giới trên bộ).

Ngày 27/12/1985 Việt Nam và Cộng

hoà nhân dân Campuchia đă kư Hiệp ước hoạch định biên giới quốc gia trên cơ sở

thoả thuận năm 1967. Thi hành Hiệp ước, hai bên đă tiến hành phân giới trên thực

địa và cắm mốc quốc giới từ tháng 4/1986 đến tháng 12/1988 được 207 km/1137 km,

tháng 1/1989 theo đề nghị của phía Campuchia, hai bên tạm dừng việc phân giới

cắm mốc.

Trên biển, ngày 7/7/1982 hai

Chính phủ kư Hiệp định thiết lập vùng nước lịch sử chung giữa hai nước và thỏa

thuận: sẽ thương lượng vào thời gian thích hợp để hoạch định đường biên giới

trên biển, lấy đường gọi là đường Brévié được vạch ra năm 1939 với tính chất là

đường hành chính và cảnh sát làm đường phân chia đảo giữa hai nước.

Với Chính phủ Campuchia thành

lập sau khi kư Hiệp ước hoà b́nh về Campuchia năm 1993 , năm 1994, 1995 Thủ

tướng Chính phủ hai nước đă thoả thuận thành lập một nhóm làm việc cấp chuyên

viên để thảo luận và giải quyết vấn đề phân giới giữa hai nước và thảo luận

những biện pháp cần thiết để duy tŕ an ninh và ổn định trong khu vực biên giới

nhằm xây dựng một đường biên giới hoà b́nh, hữu nghị lâu dài giữa hai nước. Hai

bên thoả thuận trong khi chờ đợi giải quyết những vấn đề c̣n tồn đọng về biên

giới th́ duy tŕ sự quản lư hiện nay.

Thực hiện thoả thuận giữa Thủ

tướng Chính phủ hai nước nhân dịp Thủ tướng Ung Huốt sang thăm Việt Nam đầu

tháng 6/1998, nhóm chuyên viên liên hơp về biên giới Việt Nam - CPC đă họp tại

Phnom Pênh từ ngày 16 - 20/6/1998. Trong cuộc họp này hai bên đă trao đổl về

việc tiếp tục thực hiện các Hiệp ước, Hiệp định về biên giới giữa hai nước đă kư

trong những năm 1982, 1983, 1985. Hai bên đă dành nhiều thời gian thảo luận một

số vấn đề về quan điểm của hai bên liên quan đến biên giới biển và biên giớl

trên bộ với mong muốn xây dựng đường biên giới giữa hai nước trở thành đường

biên giới hoà b́nh, hữu nghị và hợp tác lâu dài.

Hai bên đă thống nhất ḱến nghị

lên Chính phủ hai nước tiến hành thành lập Uỷ ban liên hơp với những nhiệm vụ:

- Soạn thảo Hiệp ước về hoạch

định biên giới biển và Hiệp ước bổ sung Hiệp ước hoạch định biên giới quốc gia

tŕnh lên chính phủ hai nước.

- Chỉ đạo việc phân giới trên

thực địa và cắm mốc quốc giới.

- Giải quyết mọi vấn đề liên

quan đến việc thực hiện Hiệp định về quy chế biên giới giữa hai nước.

Qua trao đổi về đường biên giới

biển, phía CPC kiên tŕ quan điểm muốn lấy đường do Toàn quyền Brévié vạch ra

tháng 1/1939 làm đường biên giới biển của hai nước.

Ta đă nói rơ là ta không chấp

nhận đường Brévié làm đường biên giới biển giữa hai nước v́:

1. Đường Brévié không phải là 1

văn bản pháp quy, chỉ là một bức thư (lettre) gửi cho Thống đốc Nam Kỳ đồng gửi

cho Khâm sứ Pháp Ở CPC. Văn bản đó chỉ có mục đích giải quyết vấn đề phân định

quyền hành chính và cảnh sát đối với các đảo, không giải quyết vấn đề quy thuộc

lănh thổ;

2. Cả hai bên không có bản đồ

đính kèm theo văn bản Brévié v́ vậy hiện nay ít nhất lưu hành 4 cách thể hiện

đường Brévté khác nhau: Đường của Pôn Pốt, đường của Chính quyền miền Nam Việt

Nam, đường của ông Sarin Chhak trong luận án tiến sỹ bảo vệ ở Paris sau đó được

xuất bản với lời tựa của Quốc trưởng Norodom Sihanouk, đường của các học giả Hoa

Kỳ.

3 . Nếu chuyển đường Brévié

thành đường biên giới biển th́ không phù hợp với luật pháp quốc tế, thực tiễn

quốc tế, quá bất lợi cho Việt Nam và nên lưu ư là vào năm 1939 theo luật pháp

quốc tế lănh hải chỉ là 3 hải lư, chưa có quy định về vùng đặc quyền về kinh tế

và thềm lục địa th́ đường Brévié làm sao có thể giải quyết vấn đề phân định lănh

hải theo quan điểm hiện nay và phân định vùng đặc quyền về kinh tế và thềm lục

địa.

Phía Việt Nam đă đề nghị hai bên

thoả thuận: áp dụng luật biển quốc tế, tham khảo thực tiển quốc tế, tính đến mọi

hoàn cảnh hữu quan trên vùng biển hai nước để đi đến một giải pháp công bằng

trong việc phân định vùng nước lịch sử, lănh hải, vùng đặc quyền kinh tế, thềm

lục địa của hai nước.

Trong thời-gian gần đây, người

ta không thấy Hà Nội thay đổi quan-điểm nào rơ-rệt.

Nếu ṭ ṃ, xin Quư Vị xem thêm một số

quan-điểm phía Cambodia, cũng posted trong site này.

Khmer exterminated the 515 Vietnamese

residents of Poulo

Panjang (Tho Chu island) in May 1975:

http://www.camnet.com.kh/cambodia.daily/selected_features/cd-14-02-04.htm

The Cambodia Daily , WEEKEND

Saturday, February 14-15, 2004

Defining Cambodia

By Michelle Vachon

The Cambodia Daily

Sixty-five years ago, a French colonial administrator made a decision on

maritime borders between

Cambodia and Cochin-China, as the southern part of Vietnam was then

called.

Jules Brevie hoped his decision would resolve, once and for all, a long dispute.

Meant to clarify which islands in the Gulf of Thailand fell under the

jurisdiction of either Cambodia or Cochin-China, Jules Brevie's administrative

notice of Jan 31, 1939, has been at the heart of all maritime border quarrels

between Cambodia and Vietnam ever since.

Every political regime in Cambodia has raised the issue, which still triggers

heated debates and often puts the two countries at odds with each other.

In the 1960s, then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk requested an international conference

to settle the matter once and for all, and to protect Cambodia's territory

through peaceful means.

No such approach suited the

Khmer Rouge, who bombarded the

Vietnamese island of Phu Quoc (Koh Trac in

Khmer) and exterminated the 515 Vietnamese residents of

Poulo

Panjang (Tho Chu island) in May 1975,

said Raoul Marc Jennar in his 1997 doctorate thesis, "Contemporary Cambodian

Borders."

The only agreements on maritime borders between Cambodia and Vietnam were signed

in July 1982. They were part of a series of pacts that were based on the Treaty

of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation signed on Feb 18, 1979Ñshortly after

Vietnam had ousted the Khmer

Rouge regime, taken over the country and installed a Hanoi-friendly government.

Valid for 25 years, terms of the agreement indicate that the 1979 treaty will be

automatically renewed for periods of 10 years, unless revoked the year before

renewal by either country, said Var Kim Hong, chairman of Cambodia's Border

Committees.

As far as he knows, no measure has been taken to annul the agreement, and it

should get renewed on Wednesday, he said.

But the renewal will not be accompanied by a new agreement on maritime borders.

In this area, negotiations continue, Var Kim Hong said.

The debate, which the Sam Rainsy Party and Funcinpec rekindled during the

national election campaign of 2003, has made strange allies.

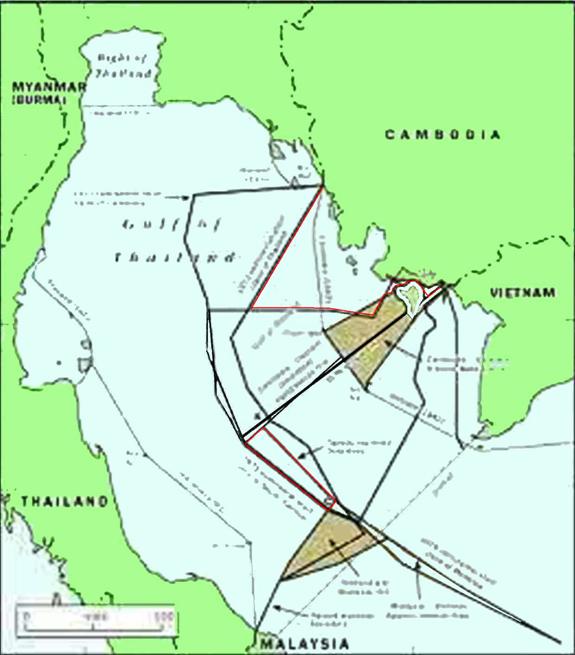

The figure of 95,000 square km, often-quoted as the waters over which Cambodia

should have jurisdiction, was given legal status during the Lon Nol regime,

Jennar said.

The administration, which had ousted then-Prince Sihanouk in 1970, issued a

decree in 1972 setting the size of the country's continental shelf and claiming

Cambodia's rights over it.

The territory covered a third of the waters claimed by Thailand, and

three-quarters of the zone claimed by Vietnam, said Jennar. The lure of possible

oil and gas contracts in the gulf prompted Cambodia and its neighbors to act

without consulting each other, he said. Cambodia and Vietnam's claims overlapped

by 60,000 square km.

Four years later, the Khmer

Rouge adopted King Sihanouk's position during their preliminary talks with the

Vietnamese, and picked the Brevie line to define the maritime borders, said

Jennar. But the Pol Pot regime soon put an end to the May 1976 meeting, and

progressively turned to arms against Vietnam, he said.

Brevie was governor general of IndochinaÑwhich included Cambodia, Laos and the

Vietnamese territoriesÑwhen he issued his notice in 1939. He was attempting to

end disagreements that had started in the 19th century.

In the late 1870s, Cochin-China Governor Le Myre de Villiers led a group of

French businessmen who replaced navy officers in the Cochin-China government,

wrote Alain Forest in his 1980 book, "Cambodia and the French Colonization." Not

only did they want land for plantations and good fishing grounds, but they also

envisioned Cambodia's annexation, he said.

Unlike Cambodia, which was an independent country with a king and government

that had requested France's protection, Cochin-China was a French colony.

Expanding Cochin-China's territory was an ambition of France.

Huynh de Verneville, the French administrator assigned to Cambodia, tried to

limit Cochin-China's expansion project, but with limited success, said Forest.

Still, Cambodia, which was caught between its two expansionist neighbors in the

19th century, extended its territory during the French Protectorate.

Using the border on land as his starting point, Brevie traced a straight line

into the Gulf of Thailand, indicating that the waters and islands north of the

line would be administered by Cambodia, and islands and waters south of it by

Cochin-China. However, because Phu Quoc had been under Cochin-China's

administration since the 1860s, he left it to Vietnam, making the line pass 3 km

north of the island.

Brevie noted that the islands close to the Cambodian coast were geographically

linked to Cambodia, and therefore should fall under its jurisdiction.

Up to then, no document had shown whether the islands had been part of Cambodia

or Cochin-China. In 1913, the French administrator of Cochin-China had said that

he could find no proof of jurisdiction, reported Sarin Chhak in his 1966 book,

"Cambodia's Borders."

Brevie set his line for the purpose of dividing administrative and police duties

among the two jurisdictionsÑhe never intended his line to be considered the

maritime border, he wrote.

Sarin Chhak said that Brevie even pointed this out in his notice by writing, "It

is understood that the above pertains only to the administration and policing of

these islands, and that the issue of the islands' territorial jurisdiction

remains entirely reserved."

However, this paragraph of Brevie's letter, printed in Sarin Chhak's book, does

not appear in the letter at the National Archives in Phnom Penh. The original

document on file consists of a cover letter with Brevie's signature, which is

attached to his letter on the dividing line; the documents are numbered 867 and

868, written in the same hand, obviously numbered one after the other.

Except for this discrepancy over the paragraph most frequently quoted to

illustrate the intent and legal value of Brevie's line, the rest of the document

is identical to the letter reproduced in Sarin Chhak's book.

In any case, the French administrators of Indochina could not know Cambodia,

Laos and Vietnam would gain their independence, and that their administrative

land and sea dividing lines would become international boundaries.

In 1957, Cambodia became the first country in the Gulf of Thailand to define its

territorial waters at a time when international laws on the subject were just

developing, said Jennar. The decree of Dec 30 set the width of the country's

territorial waters at five nautical miles, or 9.26 km; and its contiguous waters

at 7

nautical miles, or 13 km. These were modest and reasonable claims, said Jennar.

Cambodia maintained its "historical rights" over Phu Quoc. In a separate letter,

Prince Sihanouk ordered the Royal Navy to protect all islands, especially

Poulo

Panjang,

Poulo Wai and Koh

Tang, whose occupation, he wrote, "are essential to the good development and

maritime future of the Port of Kompong-Som."

In 1960, Cambodia was the first country in the Gulf to sign the 1958 Geneva

Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone. The National Assembly

approved it in 1963, but it wasn't enacted until 1968.

In 1969, Cambodia extended its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles, or 22.2

km, which is in accordance with international laws.

The decree of 1982 redefined the country's baseline from which territorial

waters are measured. Instead of being close to the shore as it was in 1957, the

baseline links Cambodia's distant islands from the Thai border to

Poulo Wai.

The document recognized for the first time that

Poulo Wai belongs to

Cambodia. It set the country's Economic Exclusive Zone and its continental

shelf, which are nearly identical, at the customary 200 nautical miles, or 370

km.

In addition, a 1982 agreement maintains all international rights to territorial

waters and the continental shelf and establishes "historic waters" on each side

of the Brevie line, a zone over which both Cambodia and Vietnam were to have

jurisdiction, and in which people from both countries would be allowed to fish.

During the first meetings of the Cambodian-Vietnamese joint border commission,

Vietnam rejected the Brevie line as a maritime border, while Cambodia insisted

on keeping it, said Alain Gascuel, who has closely followed the work of the

commission.

Does the work of the commission move in an uncommonly slow fashion? Not really,

said Martin Pratt, director of the International Boundaries Research Unit for

the University of Durham in the United Kingdom. "Maritime boundary delimitation

can be a difficult process at the best of times. In semi-enclosed seas with lots

of islands, the challenges are even greater."

Before the start of the negotiations, Cambodia filed a complaint with the UN

against Vietnam and Thailand; in 1997, their governments signed an agreement

defining their continental shelves and economic zones in the Gulf of

ThailandÑwithout consulting Cambodia. Incidents like this one have convinced Lao

Mong Hay, the head of the Legal Unit at the Center for Social Development, that

Cambodia should submit its case to an international court or organization whose

decision would be binding, he said.

He also believes that, unless Cambodia is in a position to manage and control

its territorial waters, having jurisdiction over portions of the Gulf of

Thailand will not mean very much.

Cambodia should invest in rebuilding its navy, and in training people to run

offshore oil and gas operations, and other maritime departments, Lao Mong Hay

suggested.

Những vùng Hải-phận Đặc-Quyền Kinh-Tế của Việt-Nam trong vịnh

Phú-Quốc. |

Chiến-Lược

Biển Đông

Chiến-Lược

Biển Đông